What are heat networks?

Heat networks are part of the UK’s plan to cut carbon emissions from heating. By connecting homes and buildings into shared systems, we can make better use of local renewable energy, reduce reliance on fossil fuels, and build a more efficient and resilient energy future.

HEAT Networks

A heat network works by generating heat in a central location and distributing it to homes and buildings through insulated pipes. Instead of each dwelling or building having its own boiler, they are supplied with ready-to-use heated water from a shared system. This makes it much more efficient and cost-effective, especially when the heat comes from sources that would otherwise go to waste.

There are three main types of heat networks: Communal/Block Heating, District heating/Micro heat grid and Regional Heat Transmission.

What is a Communal or Block Heat

Network?

Communal heating, also known as block heating, is where a single central energy system provides heating and hot water to all the homes and spaces in one building. Instead of every flat having its own boiler, heat is produced in a central plant and distributed through insulated pipes to each home. Inside each flat, a Heat Interface Unit (HIU) gives residents control over their own heating and hot water, just like a boiler would, but with fewer parts to maintain.Typical examples of buildings served by such systems: multi-residential apartments, care homes, and student accommodation blocks.

What is a District Heat Network or Micro Heat Grid?

Generally, these systems are spread over a specific area, whether it be a university campus, village, town or a district as part of a larger city. Heat for domestic hot water and space heating is generated in a central location and distributed to homes and buildings through insulated pipes in the ground. Instead of each dwelling or building having its own boiler or energy centre, they are supplied with ready-to-use heated water from a shared system.Typical examples of buildings served by such systems: Public buildings, hospitals, schools, existing and new low-density and high-density dwellings

WHAT IS REGIONAL HEAT TRANSMISSION?

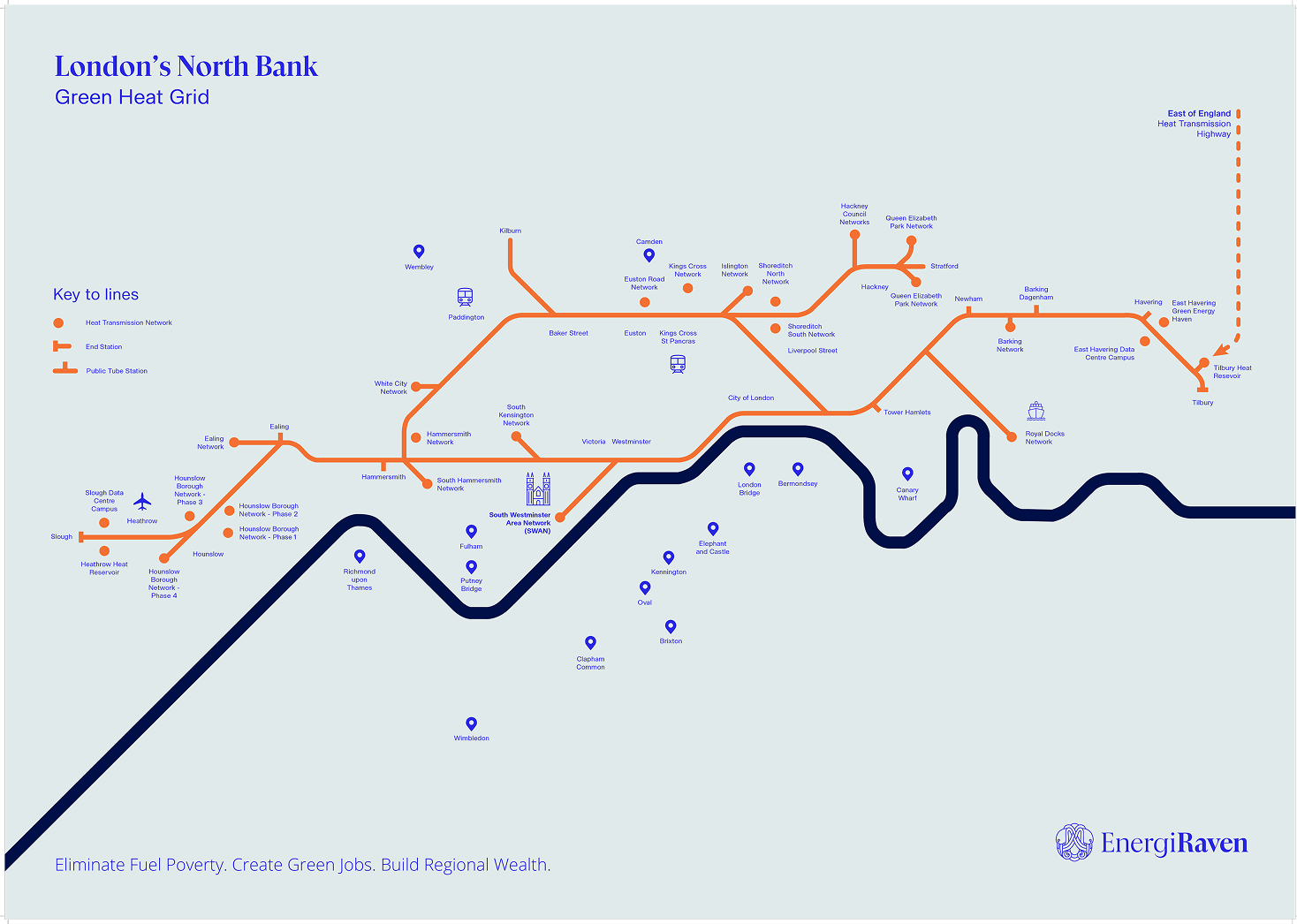

Heat Transmission Highways can harvest commercial and industrial waste heat, heat from surplus renewable power generation, and freely available renewable heat from coal mines. This heat can then be transported to villages, towns, and cities, providing a sustainable and efficient solution for heating needs.

By transporting low-cost, zero-carbon heat from areas of surplus to where it’s needed most, we have a powerful opportunity to build community wealth, create green jobs, and eliminate fuel poverty.

YOUR QUESTIONS. STRAIGHT ANSWERS.

Because heating is the single biggest source of carbon emissions in most towns and cities. Heat networks provide a practical and cost-effective way for councils to meet net zero targets, tackle fuel poverty, and keep more energy spending within the local economy.

Building a heat network does require upfront investment in infrastructure, but they are long-term assets that pay back over decades. Funding support is available through central government schemes. Although not ideal, councils often partner with private investors to reduce public capital risk.

Ownership can vary. Some are council-led and publicly owned, others are run by private companies, housing associations, or joint ventures. Increasingly, councils are taking a role as anchor partners, ensuring networks are designed in the public interest while allowing specialist operators to manage day-to-day running.

By buying heat in bulk and using local low-cost sources (such as waste heat or renewables), heat networks can keep bills stable and protect residents from volatile gas prices. Councils can also set rules to make sure the benefits are passed fairly to households.

When properly designed and maintained, heat networks can be more reliable than individual gas boilers, with fewer breakdowns and easier maintenance. Modern networks include backup systems to ensure continuity of supply.

- Visible local action on climate commitments

- Creation of green jobs and apprenticeships

- Attracting investment into the area

- Stable energy bills for residents and public buildings

- Resilience against volatile global fuel markets

Heat networks work best in places with a relatively high building density (such as villages (micro-grids), towns, cities, or campuses), or where there are local renewable or waste heat sources (like data centres, factories, rivers, or mines), however heat from these sources can effectively be moved over entire regions.

Heat pumps are a vital part of the net zero transition, but they work best at large-scale when connected into a heat network. Networks allow us to use larger, more efficient heat pumps and integrate many sources of renewable and waste heat that individual households can’t access. Individual heat pumps are preferred for rural or isolated buildings.

Councillors can:

- Support inclusion of heat networks in local planning policy

- Help identify anchor loads (like schools, hospitals, leisure centres)

- Locate sources of waste or freely available heat, as well as, heat that can be generated and stored from excess renewable electricity generation to avoid curtailment

- Champion local engagement and resident communication

- Unlock funding opportunities and political support

Examples include networks in Bristol, Leeds, Nottingham, Manchester, and Edinburgh. Many councils are now developing their own projects, and site visits can usually be arranged to see how they operate in practice.